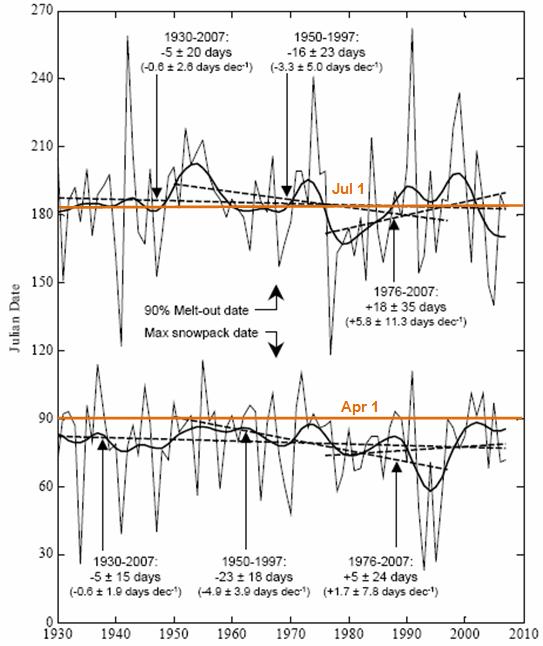

These patterns described for the North Cascades are concurrent with anomalously low snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, and thus part of a broader trend toward reduced snowpack in western North America. Extreme flips in snowpack conditions (year-to-year changes between 95th percentiles) during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were anomalous within the context of the record. Not only is the twentieth–twenty-first century period characterized by the rapid decline in snowpack conditions, it is also highly volatile. This decline culminated in the 2014–2016 northern Cascade Mountains snow drought, which is unprecedented within the context of the last 400 years. The reconstruction is characterized by considerable interannual- to interdecadal-scale variability, but a conspicuous decline emerged in the mid-1970s and accelerated through to the most recent years of the record to levels below the pre-industrial envelope of variability. The 2014–2016 snow drought, especially snow conditions during the 2015 winter, across the northern Cascades is unprecedented within the context of the last 400 years. Yet, the most conspicuous feature is a decline that began in the mid-1970s concurrent with a shift to above-average air temperature which is accelerated through to the most recent years of the record. The reconstruction is characterized by considerable interannual- to interdecadal-scale variability. 400 years that accounts for 62% of the instrumental period variability. Here, we use a network of 30 tree-ring chronologies to reconstruct April 1 snowpack in the northern Cascade Mountains (Washington, USA) over the past ca. Given the brevity of observational records, the extent to which these recent trends exceed historical ranges of variability remains poorly understood.

In recent decades, snow water equivalent (snowpack) has declined dramatically, culminating in record lows along the northern Cascade Range, USA, during the winters of 20. So, the chance of accumulating snow and it lasting in the valley would be pretty small.Cool-season precipitation is a critical component of western North American water supplies. Toad temperatures are getting warmer throughout the day. "We're getting later in the season," Nisbet said. Nisbet says the Cascade Mountains will likely get even more snow into late spring, although areas like the Wenatchee Valley won't see much more accumulation. The runoff of snow also helps with river flow and reducing the severity of wildfires.

The last report from the National Water and Climate Center showed the Central Columbia Basin at 89% of normal snowpack.Ī buildup of snowpack is needed for water supply and irrigation in the region.

#North cascadea snowpack update#

Nine inches of snow was reported at I-90 Snoqualmie Pass on Sunday, and five additional inches as of early Monday.Īn update on snowpack levels in the mountains should be released Monday. There were six more inches reported at the pass as of early Monday morning. Sunday's dump of 23 inches is the biggest single day of snowfall at Stevens Pass since winter began. The top day for accumulation in that stretch was 19 inches on Jan. Stevens Pass received 68.5 inches of snow over a six-day period between Jan. "They haven't seen that much snow since the pass was closed in early January." National Weather Service meteorologist Laurie Nisbet says Stevens Pass received 23 inches of snow overnight Saturday into Sunday, which is significant.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)